[The following description, edited slightly, comes from an article from the ‘The Forum’ in 1916. Although the first Zeppelin attack on England occurred on the 19 -20 January 1915 at Yarmouth,

I thought Perriton Maxwell’s 100 year old account would give the reader an insight into the impact this new form of warfare had on the non-combatants … and its chilling human toll on ‘old Tom Chambers’.]

… for twenty-six years old Tom Cumbers had held his job as switch man at the Walthamstow railroad junction where the London-bound trains come up from Southend to London. It was an important post and old Tom filled it with stolid British efficiency. He was a kindly man who felt himself an integral part of the giant railroad system that employed him and had few interests beyond his work, family and the little four-room tenement which he called home.

Walthamstow was a working-class suburb on the edge of Epping Forest, the supposed scene of Robin Hood’s adventures, and home to some ten thousand wage-strugglers. It was here on a sweltering night in August 1915 that a new form of warfare came to the shores of England, and to the innocent inhabitants of this small British town.

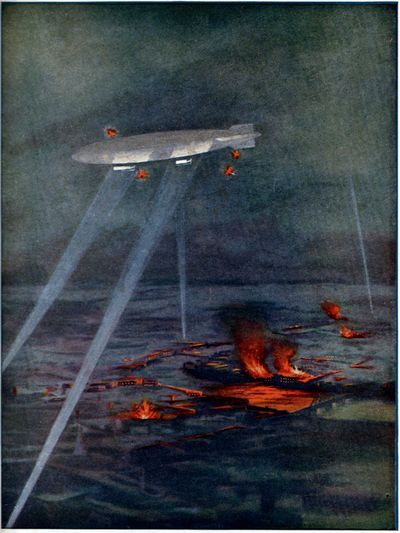

Shortly after eleven o’clock on the 17 August the whole town was at rest and blanketed in the quiet still aura of a suburban summer’s night. While there was no disturbance in the clouds themselves there was among them something very active, something that drilled its way through them with a muffled whirring, something that was oblong and lean and light of texture, that was ominous and menacing for all its buoyancy. The sound it made was too high up, too thickly shrouded by clouds, to determine its precise position. It gave forth a breathing of persistent, definite rhythm.

This was plainly not the wing-stroke of a nocturnal bird; for no bird, big or little, could advertise its flight in such perfect pulsation. And yet it was a bird, a Gargantuan, man-made bird with murder in its talons, which had penetrated the English Coast and then, dropping lower, had sought and found through the haze the tiny train whose locomotive had just fluted its brief salutation to Walthamstow.

To the men on the Zeppelin L10 were the first on the first naval launched airship to reach London. The string of cars far down under their feet, with its side-flare from lighted windows, its engine’s headlamp and its sparks, had proved a providential pilotage. They knew that this train was on the main line, and that it would lead them straight to the great Liverpool Street Station, and that was London, and it was London wharves and ammunition works along the Thames that they planned to obliterate.

But the moist clouds which aided so materially in hiding the Zeppelin’s presence from below also worked for its defeat, in so far as its ultimate objective was concerned, for to keep the guiding train in view it was compelled to travel lower and yet lower – so low, indeed, as to make it a target.

Somehow, by sight or intuition or the instant commingling of the two, old Tom Cumbers became aware of the danger above him; for he sprang to his switch, shut off all the cheery blue and white lights along “the line” and swung on with a mighty jerk the ruby signal of danger.

The engineer in the on-rushing train jammed down his brakes and brought up his locomotive with a complaining, grinding moan, a hundred yards beyond Walthamstow station. Instantly the Germans lost their trail of fire as their involuntary guide had disappeared in the gloom and the long journey had suddenly become fruitless; their peril from hidden British guns and flying scouts was increased tenfold. As the hot surge of disappointment swept the airmen the commander, forgetting his sense of military effectiveness, steered over the shabby roofs of Walthamstow and, at less than two thousand feet, unloosed his iron dogs of destruction.

Somewhere near the town’s centre the earth split and roared apart.

The world reeled and a brain-shattering crash compounded of all the elements of pain and hurled from the shoulders of a thousand thunderclaps smote the senses. It was a blast of sickening fury.

More terrible than the first explosion was, or seemed, this second one. It mowed down half a hundred shrieking souls. And it was curious to note the lateral action of the blast when it hit a resisting surface. Dynamite explodes with a downward or upward force, lyddite and nitro-glycerine, but the bombs hurled on Walthamstow contained ingredients which released a discharge which swept all things from it horizontally, in a quarter-mile, lightning sweep, like a scythe of flame.

A solid block of shabby villas was laid out as flat as your palm by the explosion of this second bomb. Scarcely a brick was left standing upright.

What houses escaped demolition around the edge of the convulsion had their doors and windows splintered into rubbish.

The concussion of this chemical frenzy was felt, like an earthquake, in a ten-mile circle. Wherever the scorching breath of the bombs breathed on stone or metal it left a sulphurous, yellow-white veneer, acrid in odor and smooth to the touch. Whole street-lengths of twisted iron railings were coated with this murderous white-wash.

At the safe distance of four thousand feet it dropped three more shells recklessly, haphazard. One of these bored cleanly through a slate-tiled roof, through furniture and two floorings and burrowed ten feet into the ground without exploding. This intact shell has since been carefully analyzed by the experts of the Board of Explosions at the British War Office.

Another bomb detonated on the steel rails of the Walthamstow tram-line and sent them curling skyward from their riveted foundations like serpentine wisps of paper.

Great cobblestones were heaved through shop windows and partitions and out into the flower-beds of rear gardens; some of the cobbles were flung through solid attic blinds and others were catapulted through brick walls a foot in thickness. A hole as big as a moving-van burned into the road at one place.

Eight bombs in all were launched on Walthamstow – two of them ineffectual.

The sixth bomb fell into a field close beside the railway line and worked a hideous wonder. It blew into never-to-be-gathered fragments all that was mortal of old Tom Cumbers, the signalman. They found only his left hand plastered gruesomely against the grassy bank of the railway cut not a hair nor button else.

References

The Death Ship in the Sky, The Forum, by Perriton Maxwell, 1916, pp. 195-200.